Bliain - Part 8

12th April 2021

Part eight of my project to make a photograph every day for a full year, or bliain in Irish. Find Part 7 here.

30th March

The biggest tides of the year occurred today. At least I think they did, I haven’t bought a tide tables for 2021 yet, but the biggest springs are usually after the vernal equinox. Either way, to mark the occasion I went for a swim with a friend at the highest stage of the tide, which happened to be an hour before sunrise. It was cold. I’ve not been swimming much recently and the sea was a lot chillier than the last time I was in at the end of February. After some hesitation (which always just makes things worse) I dived in and came up screaming and roaring into the dark sky above me. Which wasn’t particularly necessary (it wasn’t that cold) but was actually very therapeutic once I got going, and I wouldn’t have done it in daylight hours for fear of somebody hearing me. I might make more of a habit of this. A swim and a scream. Might start a trend. Almost six hours later I availed of the low tide to get into a sea cave that a friend had told me about. I’m kind of shocked I hadn’t been in there before to be honest, given how much time I’ve spent very near to it. It’s quite deep and narrow, with two holes in the ceiling and some absolutely gorgeous colours on the walls, rich and vivid under the glossy seepage. You don’t actually need an unusually low tide to get into it, nor do you need a particularly big high tide to go swimming, but nonetheless I enjoyed marking the phenomenon of the moon-pulled sea with some appropriate activities. What has any of that got to do with this photograph? Absolutely nothing. I had all those words written by the afternoon, to go along with a photo from the cave, but while making dinner this evening I noticed out the kitchen window that the hill behind the back garden seemed to be the only clear point of ground in an otherwise foggy landscape. I took the pot off the hob and got my hiking boots on. Half an hour after closing the front door I was stood on the peak of this humble hill, surrounded by an unbroken ring of cloud and fog and shifting mists. What a gift of an evening! And since conditions like this aren’t so common I thought I’d use this dreamy selfie for today’s image, and save the dark, damp cave for some other day when the sky doesn’t open up and present me with such heavenly scenes.

31st March

Looking out from Poll na gColúr Beag (Small Hole of the Rock Dove) on Clogher Strand. I came here looking for a carving of a sailboat that was etched into a stone outside the cave a century or so ago, and found it easily, much to my surprise. Having read about it in Seán Mac an tSíthigh’s storied Instagram post I expected to have to go digging, but the sand was about five feet lower today than when he first found it. I had planned on making a picture of the carving but the rock was so slick with water (it was raining all morning) that the reflections made it tricky to get a decent photograph. And so here’s a picture from the cave itself (which isn’t the cave mentioned yesterday). Rock doves frequently nest in sea caves like this, and I’ve heard of similar places with similar names in Irish. Anybody who’s had their heart jump out of their chest with the fright when one of those birds unexpectedly explodes from its ledge to escape your intrusion doesn’t forget about it quickly, and such frights are probably the seed of many of the placenames associated with rock doves. Before leaving for home I met two women in the car park who asked if I’d seen the eel-like creature in the sandy pool. One of them had been in before me and noticed a reddish fish dart into the shadow as she approached. Sadly I hadn’t, but it sounded more intriguing than somebody noticing something similar out on the beach. Perhaps it’s the sense of eeriness found in these kinds of dark, closed spaces that makes any animal encounter in a cave all the more memorable.

1st April

The first day of April, and what a day it was. The sun was shining and the air was warm despite a steady breeze. I spent most of the day outside, cycling and walking and then reading in the garden later on. It seemed too nice to bother doing anything that could be even remotely conceived of as work, so I didn’t make much of an effort with the camera. This simple photo is of a speedwell flower in the garden grass, which I’ll sadly have to cut soon to keep the landlord happy. We could all badly do with more weather like this in Ireland right now. The pandemic made it feel like a particularly long winter, but thankfully that season is more or less behind us at this stage. And hopefully the worst of the pandemic is too.

2nd April

Another blue sky day that had to be spent outdoors. After getting knee surgery last year I didn’t really expect to do much bouldering ever again, given that any form of impact on my bad knee is best avoided and this style of climbing involves lots of falling. But today I convinced myself it’d be alright to go out for some easy clambering around, and it was an absolutely perfect day to do so. I climbed some of the more mellow problems in Com a’ Lochaigh, but of course that just lead to being excited about being out climbing again, and I ended up trying some of the more difficult lines. Thankfully my knee held up fine, though my shoulders and fingers definitely got a bit of a shock after so long since last being used like that. After finishing up with the few areas I’d already been to I went for a wander along the other side of the valley to see if I could find anything new. And what a treat it was to stumble on this perfect boulder - a gently overhanging wall, just the right height, a safe, soft landing, and an obvious line of spaced-out holds. In good bouldering style the moves felt powerful and dynamic and never really eased up (though that’s probably just my weakened state talking). I didn’t actually expect to do it given how unfit for climbing I feel these days, but somehow I managed to get myself over the top. I was totally gripped trying to pull over the lip. It was mega; the full package. And as if to mark the occasion a wheatear perched on top of the boulder before I left. It was my first sighting of this welcome summer visitor this year, and was a real joy to see. I found three more short but quite nice lines a bit later in the day too. Most of my best climbing memories are from this time of year, and it was really really nice to be out grappling with rocks in a gorgeous place again, despite knee injuries and pandemics.

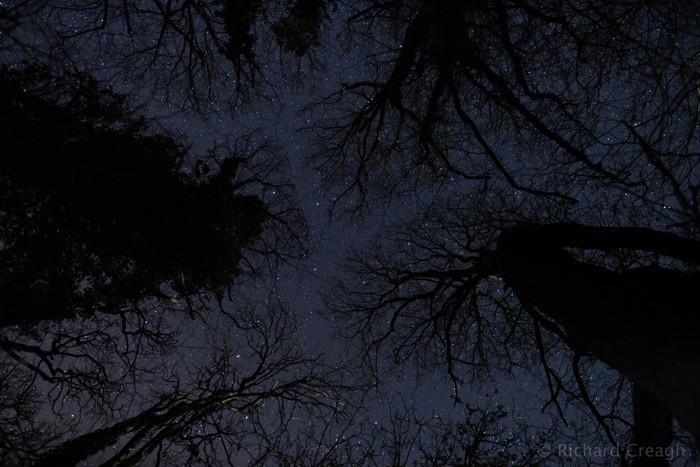

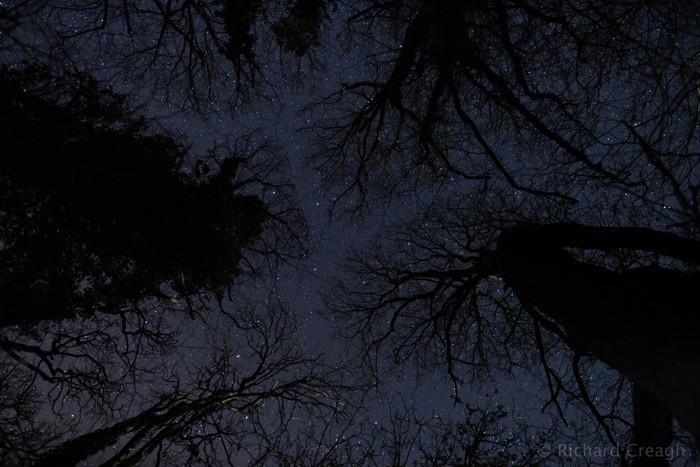

3rd April

The fine weather continues, and with the wind forecasted to slacken off by evening I had this image in mind throughout the day. It’s been on my list for awhile now, but getting a clear, moonless, windless night before the summer growth of leaves covers over most of the view wasn’t guaranteed, so I was grateful to get this opportunity today. It’s one thing to lie back and look at the stars while out in the open, but doing so in a woodland still bare from winter is a different kind of thing that I find very special. Just being in the woods at night at all is very atmospheric, but it’s definitely nice to stare up through the reaching branches of big trees and see the sky full of stars.

4th April

After a perfectly calm night I woke before dawn and quickly scrambled to get my kayaking gear ready to be on the water for sunrise. Basking sharks had been seen in Ventry Harbour over the past few days and with an exceptionally fine sea forecast I was excited to see if I could spot one while out for a paddle. The following five hours were among the best I’ve ever spent kayaking, with sightings of three sharks, a minke whale, a porpoise and a lone common dolphin, and my first encounters with Manx shearwaters this year. The sea is starting to come alive again, as can be seen in the thick plankton growth in this photo. Just like the plants on land are starting to green up as the sun gets higher in the sky, so too are the photosynthesizing plant plankton known as phytoplankton, producers of half the world’s oxygen. These tiny beings form the basis of the marine food chain, feeding grazing plankton and both small and big fish (including the basking sharks). The fish are then eaten by some of the bigger species of fish, as well as by birds and marine mammals such as seals, whales and dolphins. The basking sharks show up to gorge on this seasonal feast, swimming around with their mouths open and filtering the plankton using their specialised gills. Though I’ve seen basking sharks plenty of times before I’d never been kayaking near to them, and it was utterly fantastic - humbling, frightening and incredibly exciting. The way they move is mesmerizing; everything is smooth and slinky, and their ability to seamlessly sink deeper or rise to the surface while still cruising along on a level plane seems like some miraculous form of levitation. Having two sharks pass by, like apparitions in the darkening depths (I always feel a little vertigo when looking down into deep, dark water from my kayak), is something I won’t forget in a hurry. I hope the sharks weren’t too put out by my presence. It’s very easy to get over-excited about these kinds of encounters and totally forget that you’re almost certainly interrupting the natural behaviour of the animals you’re obsessing over, which isn’t exactly sound is it? Though at one point this shark, which was at least as long as my kayak (16.5ft) and had a dorsal fin as high as my shoulder as I was sat in the water, started following me, and my idea of who was disturbing who was flipped on its head. Basking sharks often swim in trains, one right behind the other. I’m not sure anybody knows why, but it could be to pick off plankton displaced by the leading shark. Whatever the reason is, this animal decided my kayak was taking the lead and it was very unnerving. When I turned the shark turned, and when I sped up the wake coming from that big dorsal fin grew bigger as the shark put on speed to keep up with me. I’ve never heard of a single incident of a human being harmed by these plankton feeders, but nonetheless, having an animal that size seemingly bearing down on you while on your own at sea in a small boat certainly gets the heart rate going.

5th April

The weather turned a lot cooler today, with a fresh northerly wind bringing the temperatures right down. I went out for a walk along the cosán behind home after breakfast, and despite the chill the relentless growth of spring was bursting from the hedgerows. There is so much interest and beauty to be found in an old, healthy hedge for much of the year, and just like the sea, they’re really starting to come alive again around now. Such is the variety of life to be seen that I couldn’t decide on any one photograph for today’s entry, so here are six! Clockwise from top right: speckled wood butterfly, St. Patrick’s cabbage, the heart-shaped leaves of wood-sorrel, wild strawberry, herb Robert and a tiny, perfectly unfurling yellow pimpernel flower. I could have added primrose, dog violet, curled-up ferns and much more to this montage. In a country almost devoid of wild land these kinds of hedges are genuinely important habitats for so many different kinds of life. Later this evening I saw my first swallows of the year while out for another walk; it was a magic moment. These natural world events, like solstices and equinoxes, the first flowers, the first sightings of migratory species like sharks and swallows, cuckoos and wheatears, and the noteworthy absence when they leave again, are all far more exciting to me than the arbitrary dates like Christmas and Easter (both of which were hijacked from more pagan beliefs and altered to suit) and New Year’s Day. They connect me to the ground I walk on and the Earth that provides everything I need. That might sound a bit left-field for some, but it is an unquestionable truth that our lives depend entirely on the natural world, of which we are a part, and not apart from.

6th April

Another cold day of northerly winds, with small showers passing, but beautiful bright sun in between. I tried three different locations for a photograph before eventually settling on this arrangement of broken rocks lit pleasingly by the last light of the day. It’s perhaps not the most exciting image, but I like the subtle earthy colours and the texture revealed on the top side of that bigger stone. It looks to me like the fossilized ripples of some ancient ocean floor, but my understanding of geology is very limited and that could be way off the mark. I did find a nice ‘traditional’ landscape composition soon after this, and I’ll try going back on a day with a bigger sea and more dramatic light. It’s the kind of ragged stretch of coast that looks best in those stormy evenings when the sun sneaks through in the last light of the day.

7th April

An aerial view of the beach at Cúl Dorcha and the scene to the northeast across Smerwick Harbour. The word Smerwick is of Norse origin. “Wick” is from the word vik, meaning harbour, and is also present in other Irish coastal placenames where the Vikings had a big influence, such as Helvick in Waterford. “Smer” comes from the Viking word for butter. Evidently the precedent for Kerry Gold’s success was set long before that global corporation’s rise to fame in the modern era. In Irish the bay is known as Cuan Ard na Caithne, the harbour of the height (hill) of the Arbutus tree. Ard na Caithne is a townland on the western shore of the bay, beneath the famous Three Sisters. I don’t know the area very well but somehow I doubt there are many, if any, Arbutus trees left there. Coming back to this photo, the villages of Baile na nGall and An Mhuiríoch can be seen on the opposite shore. The big headland in the back left is Ceann Bhaile Dháith, the next along to the right is Binn Bhaile Reo, and after that starts the Brandon Mountain Range. I’ll refrain from naming each of the individual peaks in that wonderful collection of hills, given that long lists of things don’t make for very good reading and the scattered catalogue of placenames already written here is probably confusing enough as it is.

8th April

A handsome pair of herring gulls lit beautifully against a raincloud. Gulls have been getting a bad reputation in the news for the past few summers as more and more people in cities like Dublin complain of their noise and brazenness. Reasonably rare occurrences like a gull stealing a sandwich are grabbed up by the media during quiet periods and sensationalized for attention. And of course this type of coverage helps people form negative opinions of something they might not have much direct experience of, like gulls, much the same as certain sectors of the media stir up hate with inflammatory headlines about immigrants for example. While working on a wildlife tour boat I’ve had people tell me gulls are “vermin” and the “rats of the sky” that should be exterminated. This is from people who have paid to come out to sea in the hope of seeing whales and seals and puffins (or sometimes not in hope but expectation, given that they’ve paid money and therefore will surely be reimbursed with sightings). Those other animals are ok it seems. They’ll look good on Instagram. But the gulls?! Disgusting creatures! We all have animals or plants we have a soft spot for or a particular interest in, but the idea of loving some things and hating others to the point that you wish to exterminate them speaks to the total lack of education on the natural world received by much of the wider population. Everything has its place and deserves a chance to live out its life (though I fully support the eradication of invasive species, which have their place, but in their native areas.) Herring gulls have suffered enormous population declines in the last few decades (as have the majority of seabirds, thanks to various forms of human disruption). The reason they appear so numerous in cities is because the lack of available food in our fished-out seas is driving more of these opportunistic birds to other areas where food is readily available, such as urban zones rich in litter. Granted, I don’t have gulls nesting on my rooftop waking me at four in the morning in midsummer, nor were any of my grandparents ever swooped on and frightened by a gull, but nonetheless, I find it sad that peoples’ reactions to these charming and resourceful birds are often so negative. And I lay part of the blame for that on fear-mongering “news” articles that seek to appeal to peoples’ most livid reactions in order to maintain an audience. I can’t see any way for the twin catastrophes of climate change and biodiversity loss to be tackled other than by educating people in how the world works, by which I mean the physical limitations of the planet when it comes to sustaining life. We’re straining these limits to breaking point very rapidly because people put more store in the opinion of economists (and remember, economics isn’t an empirical science, it’s a whole lot of guesswork really) than in climate, water, agriculture and fisheries scientists who gather real world, measurable data. And the data are grim. It’s utterly absurd that we’ve got to this point of living so out of touch with reality. It blows my mind and gets me down every single day. I think the generations coming up will be a lot more aware of these issues, but it’s hard to believe we’ll make the necessary changes until catastrophe leaves us no other choice. I hope I’m wrong about that.

9th April

Yesterday’s seemingly innocuous photo of two gulls certainly led me on a bit of a rant, but I think if something flows so easily while writing it’s because it was already in you waiting to be let out. Today I’ll keep it less existential, or I’ll try at least. This is a close up of a lichen known as crab-eye lichen. Lichens may seem like some of the least interesting things imaginable but they often form very interesting patterns when viewed up close. And they’re capacity to fascinate doesn’t stop with surface appearances. I’m reading Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake at the moment and learning a lot about how life on Earth wouldn’t be anything like what it is today if it weren’t for fungi. Lichens are a coming together of a fungus and alga, and sometimes bacteria, and often more than one species of each of these life forms. As such they blur the boundaries of what it means to be an individual and make a mockery of the rigid and binary classification systems preferred by the majority of scientists to date. The individuals of these otherworldly partnerships can generally manage life on their own when environmental circumstances are good, but when conditions are limiting and it makes sense to work together for the mutual benefit of everything involved lichens are formed. The fungi provide a structure as well as the ability to ‘mine’ certain minerals from the surface the lichen is attached to, and the algae can photosynthesize, producing carbon which all parties can feed on. Lichens are generally the first on the scene after new land is formed from volcanic activity, and are an important first step in making bare ground habitable for new life. Through breaking down the volcanic rock they begin the slow process of soil creation, loosening essential minerals that provide fertility for the slowly developing substrate that plants will eventually be able to take root in. And once plants are in the potential for a healthy and diverse ecosystem is huge. Some lichens are also incredibly resilient to stress and extreme environmental conditions. Certain species have been brought to space and exposed to the open atmosphere, where unfiltered UV rays are highly damaging, and temperatures can fluctuate from +120 Celsius to -120 Celsius between light and shade. After being rehydrated back down on Earth some lichens were able to start photosynthesizing again. They are a model for the strength of teamwork and partnership. And before I get into any philosophizing about that idea I’ll just recommend you read that excellent, mind-expanding book instead.

10th April

Dingle lighthouse under the Milky Way on a breezy, freezing, but beautifully clear night. Thanks to my friend Jaro for loaning me a nice fast and wide lens for this scene. The composition is a total rip off of his own idea from a few years ago too, which he once framed over dimmable LEDs so that the whole picture glowed like a TV screen in a dark room. It was one of the most creative ways I’ve ever seen of presenting a printed photograph. I’m not particularly interested in night sky photography myself, it generally requiring a higher standard of gear than I’ve ever owned, as well as a lot of computer time afterwards if you really want to do it right. It’s also incredibly difficult to reproduce scenes as your eyes saw them, which is mostly what I’m interested in for my own photography. Even this image, which is fairly boring by most astro-photographer’s standards, is way brighter than normal, with many times more stars on show than any human could actually see for themselves at night. By leaving the camera’s shutter open for long stretches of time the sensor picks up light our eyes can’t detect, giving us a view into the world beyond that which are senses are capable of seeing. I wonder if nocturnal animals, with their big, light-catching eyes, see the night skies like this? Even as a human it’s a wondrous thing to stare up into the heavens at night. To image how other creatures see the world with better eyes capable of taking in more light, as well as different types of light (lots of creatures can see UV light) is as mind-boggling as trying to comprehend all the stars in the sky.

11th April

Spring is charging ahead at a pace that’s hard to keep up with, and despite my attempts to keep photographing the various plants that represent the time of year I feel I’m bound to miss out on many of the seasonal markers. Blackthorn is one I can’t overlook though. This common hedgerow tree is unusual in that it flowers before it puts on leaves, and the bright white of its blossom against the dark colour of the wood is very striking on trees that bloom heavily. Blackthorn has a lot of folklore associated with it, or at least it used to in the days of old. According to Niall Mac Coitir’s book on the mythology of Ireland’s trees it used be believed that carrying a blackthorn stick was a good way to ward off the fairies if you were out walking at night. But using a blackthorn stick to cause harm to an animal would only bring bad luck, as the famer who struck his best cow in a fit of rage found out. Despite this latter point, blackthorn was the timber of choice for shillelaghs used in faction fighting, being incredibly hard and tough. With its sharp thorns and propensity to grow in dense thickets, blackthorn used to be planted for hedging, providing an almost impenetrable barrier for any livestock. I have heard of gardeners losing eyes while cutting back blackthorn. These days farmers put up barbed wire instead of trees, and nearly nobody is planting hedging. If they are it’s often some lifeless, non-native evergreen thing like Griselinia. In a human-dominated world what is to become of the trees and plants that have lost their magic with the dying out of folk beliefs, and for which humans find no use anymore?

12th April

The fine weather continues, still cooler than might be expected but mostly dry and bright. All the blue sky weather of the last two weeks or so has been nice to be out in but as most landscape photographers will tell you, it’s pretty boring when it comes to making interesting images of the wider world. Hence, most of my photos from the last while have been focused on the smaller details in the landscape, and with so many flowering plants starting to show around now that is no bad thing at all. So here’s another bonus photo for today; these unfurling ferns are changing from one day to the next, and while I’m sure I could find a similar one of each for tomorrow’s image I’m also happy to present both here together. Many ferns at this time of year are like little bunches of slow yawns stretching out of the soil after waking from the winter underground. The specimen on the left is a hart’s tongue fern. I always assumed it was christened for somebody with the surname Hart (and wondered about their tongue) but apparently hart was an old world for a male red deer. The fern on the right is bracken, looking for all the world like a personified cartoon version of itself with its head thrown back and arms outstretched in a deep yawn after its long sleep.

Find Part 9 here

30th March

The biggest tides of the year occurred today. At least I think they did, I haven’t bought a tide tables for 2021 yet, but the biggest springs are usually after the vernal equinox. Either way, to mark the occasion I went for a swim with a friend at the highest stage of the tide, which happened to be an hour before sunrise. It was cold. I’ve not been swimming much recently and the sea was a lot chillier than the last time I was in at the end of February. After some hesitation (which always just makes things worse) I dived in and came up screaming and roaring into the dark sky above me. Which wasn’t particularly necessary (it wasn’t that cold) but was actually very therapeutic once I got going, and I wouldn’t have done it in daylight hours for fear of somebody hearing me. I might make more of a habit of this. A swim and a scream. Might start a trend. Almost six hours later I availed of the low tide to get into a sea cave that a friend had told me about. I’m kind of shocked I hadn’t been in there before to be honest, given how much time I’ve spent very near to it. It’s quite deep and narrow, with two holes in the ceiling and some absolutely gorgeous colours on the walls, rich and vivid under the glossy seepage. You don’t actually need an unusually low tide to get into it, nor do you need a particularly big high tide to go swimming, but nonetheless I enjoyed marking the phenomenon of the moon-pulled sea with some appropriate activities. What has any of that got to do with this photograph? Absolutely nothing. I had all those words written by the afternoon, to go along with a photo from the cave, but while making dinner this evening I noticed out the kitchen window that the hill behind the back garden seemed to be the only clear point of ground in an otherwise foggy landscape. I took the pot off the hob and got my hiking boots on. Half an hour after closing the front door I was stood on the peak of this humble hill, surrounded by an unbroken ring of cloud and fog and shifting mists. What a gift of an evening! And since conditions like this aren’t so common I thought I’d use this dreamy selfie for today’s image, and save the dark, damp cave for some other day when the sky doesn’t open up and present me with such heavenly scenes.

31st March

Looking out from Poll na gColúr Beag (Small Hole of the Rock Dove) on Clogher Strand. I came here looking for a carving of a sailboat that was etched into a stone outside the cave a century or so ago, and found it easily, much to my surprise. Having read about it in Seán Mac an tSíthigh’s storied Instagram post I expected to have to go digging, but the sand was about five feet lower today than when he first found it. I had planned on making a picture of the carving but the rock was so slick with water (it was raining all morning) that the reflections made it tricky to get a decent photograph. And so here’s a picture from the cave itself (which isn’t the cave mentioned yesterday). Rock doves frequently nest in sea caves like this, and I’ve heard of similar places with similar names in Irish. Anybody who’s had their heart jump out of their chest with the fright when one of those birds unexpectedly explodes from its ledge to escape your intrusion doesn’t forget about it quickly, and such frights are probably the seed of many of the placenames associated with rock doves. Before leaving for home I met two women in the car park who asked if I’d seen the eel-like creature in the sandy pool. One of them had been in before me and noticed a reddish fish dart into the shadow as she approached. Sadly I hadn’t, but it sounded more intriguing than somebody noticing something similar out on the beach. Perhaps it’s the sense of eeriness found in these kinds of dark, closed spaces that makes any animal encounter in a cave all the more memorable.

1st April

The first day of April, and what a day it was. The sun was shining and the air was warm despite a steady breeze. I spent most of the day outside, cycling and walking and then reading in the garden later on. It seemed too nice to bother doing anything that could be even remotely conceived of as work, so I didn’t make much of an effort with the camera. This simple photo is of a speedwell flower in the garden grass, which I’ll sadly have to cut soon to keep the landlord happy. We could all badly do with more weather like this in Ireland right now. The pandemic made it feel like a particularly long winter, but thankfully that season is more or less behind us at this stage. And hopefully the worst of the pandemic is too.

2nd April

Another blue sky day that had to be spent outdoors. After getting knee surgery last year I didn’t really expect to do much bouldering ever again, given that any form of impact on my bad knee is best avoided and this style of climbing involves lots of falling. But today I convinced myself it’d be alright to go out for some easy clambering around, and it was an absolutely perfect day to do so. I climbed some of the more mellow problems in Com a’ Lochaigh, but of course that just lead to being excited about being out climbing again, and I ended up trying some of the more difficult lines. Thankfully my knee held up fine, though my shoulders and fingers definitely got a bit of a shock after so long since last being used like that. After finishing up with the few areas I’d already been to I went for a wander along the other side of the valley to see if I could find anything new. And what a treat it was to stumble on this perfect boulder - a gently overhanging wall, just the right height, a safe, soft landing, and an obvious line of spaced-out holds. In good bouldering style the moves felt powerful and dynamic and never really eased up (though that’s probably just my weakened state talking). I didn’t actually expect to do it given how unfit for climbing I feel these days, but somehow I managed to get myself over the top. I was totally gripped trying to pull over the lip. It was mega; the full package. And as if to mark the occasion a wheatear perched on top of the boulder before I left. It was my first sighting of this welcome summer visitor this year, and was a real joy to see. I found three more short but quite nice lines a bit later in the day too. Most of my best climbing memories are from this time of year, and it was really really nice to be out grappling with rocks in a gorgeous place again, despite knee injuries and pandemics.

3rd April

The fine weather continues, and with the wind forecasted to slacken off by evening I had this image in mind throughout the day. It’s been on my list for awhile now, but getting a clear, moonless, windless night before the summer growth of leaves covers over most of the view wasn’t guaranteed, so I was grateful to get this opportunity today. It’s one thing to lie back and look at the stars while out in the open, but doing so in a woodland still bare from winter is a different kind of thing that I find very special. Just being in the woods at night at all is very atmospheric, but it’s definitely nice to stare up through the reaching branches of big trees and see the sky full of stars.

4th April

After a perfectly calm night I woke before dawn and quickly scrambled to get my kayaking gear ready to be on the water for sunrise. Basking sharks had been seen in Ventry Harbour over the past few days and with an exceptionally fine sea forecast I was excited to see if I could spot one while out for a paddle. The following five hours were among the best I’ve ever spent kayaking, with sightings of three sharks, a minke whale, a porpoise and a lone common dolphin, and my first encounters with Manx shearwaters this year. The sea is starting to come alive again, as can be seen in the thick plankton growth in this photo. Just like the plants on land are starting to green up as the sun gets higher in the sky, so too are the photosynthesizing plant plankton known as phytoplankton, producers of half the world’s oxygen. These tiny beings form the basis of the marine food chain, feeding grazing plankton and both small and big fish (including the basking sharks). The fish are then eaten by some of the bigger species of fish, as well as by birds and marine mammals such as seals, whales and dolphins. The basking sharks show up to gorge on this seasonal feast, swimming around with their mouths open and filtering the plankton using their specialised gills. Though I’ve seen basking sharks plenty of times before I’d never been kayaking near to them, and it was utterly fantastic - humbling, frightening and incredibly exciting. The way they move is mesmerizing; everything is smooth and slinky, and their ability to seamlessly sink deeper or rise to the surface while still cruising along on a level plane seems like some miraculous form of levitation. Having two sharks pass by, like apparitions in the darkening depths (I always feel a little vertigo when looking down into deep, dark water from my kayak), is something I won’t forget in a hurry. I hope the sharks weren’t too put out by my presence. It’s very easy to get over-excited about these kinds of encounters and totally forget that you’re almost certainly interrupting the natural behaviour of the animals you’re obsessing over, which isn’t exactly sound is it? Though at one point this shark, which was at least as long as my kayak (16.5ft) and had a dorsal fin as high as my shoulder as I was sat in the water, started following me, and my idea of who was disturbing who was flipped on its head. Basking sharks often swim in trains, one right behind the other. I’m not sure anybody knows why, but it could be to pick off plankton displaced by the leading shark. Whatever the reason is, this animal decided my kayak was taking the lead and it was very unnerving. When I turned the shark turned, and when I sped up the wake coming from that big dorsal fin grew bigger as the shark put on speed to keep up with me. I’ve never heard of a single incident of a human being harmed by these plankton feeders, but nonetheless, having an animal that size seemingly bearing down on you while on your own at sea in a small boat certainly gets the heart rate going.

5th April

The weather turned a lot cooler today, with a fresh northerly wind bringing the temperatures right down. I went out for a walk along the cosán behind home after breakfast, and despite the chill the relentless growth of spring was bursting from the hedgerows. There is so much interest and beauty to be found in an old, healthy hedge for much of the year, and just like the sea, they’re really starting to come alive again around now. Such is the variety of life to be seen that I couldn’t decide on any one photograph for today’s entry, so here are six! Clockwise from top right: speckled wood butterfly, St. Patrick’s cabbage, the heart-shaped leaves of wood-sorrel, wild strawberry, herb Robert and a tiny, perfectly unfurling yellow pimpernel flower. I could have added primrose, dog violet, curled-up ferns and much more to this montage. In a country almost devoid of wild land these kinds of hedges are genuinely important habitats for so many different kinds of life. Later this evening I saw my first swallows of the year while out for another walk; it was a magic moment. These natural world events, like solstices and equinoxes, the first flowers, the first sightings of migratory species like sharks and swallows, cuckoos and wheatears, and the noteworthy absence when they leave again, are all far more exciting to me than the arbitrary dates like Christmas and Easter (both of which were hijacked from more pagan beliefs and altered to suit) and New Year’s Day. They connect me to the ground I walk on and the Earth that provides everything I need. That might sound a bit left-field for some, but it is an unquestionable truth that our lives depend entirely on the natural world, of which we are a part, and not apart from.

6th April

Another cold day of northerly winds, with small showers passing, but beautiful bright sun in between. I tried three different locations for a photograph before eventually settling on this arrangement of broken rocks lit pleasingly by the last light of the day. It’s perhaps not the most exciting image, but I like the subtle earthy colours and the texture revealed on the top side of that bigger stone. It looks to me like the fossilized ripples of some ancient ocean floor, but my understanding of geology is very limited and that could be way off the mark. I did find a nice ‘traditional’ landscape composition soon after this, and I’ll try going back on a day with a bigger sea and more dramatic light. It’s the kind of ragged stretch of coast that looks best in those stormy evenings when the sun sneaks through in the last light of the day.

7th April

An aerial view of the beach at Cúl Dorcha and the scene to the northeast across Smerwick Harbour. The word Smerwick is of Norse origin. “Wick” is from the word vik, meaning harbour, and is also present in other Irish coastal placenames where the Vikings had a big influence, such as Helvick in Waterford. “Smer” comes from the Viking word for butter. Evidently the precedent for Kerry Gold’s success was set long before that global corporation’s rise to fame in the modern era. In Irish the bay is known as Cuan Ard na Caithne, the harbour of the height (hill) of the Arbutus tree. Ard na Caithne is a townland on the western shore of the bay, beneath the famous Three Sisters. I don’t know the area very well but somehow I doubt there are many, if any, Arbutus trees left there. Coming back to this photo, the villages of Baile na nGall and An Mhuiríoch can be seen on the opposite shore. The big headland in the back left is Ceann Bhaile Dháith, the next along to the right is Binn Bhaile Reo, and after that starts the Brandon Mountain Range. I’ll refrain from naming each of the individual peaks in that wonderful collection of hills, given that long lists of things don’t make for very good reading and the scattered catalogue of placenames already written here is probably confusing enough as it is.

8th April

A handsome pair of herring gulls lit beautifully against a raincloud. Gulls have been getting a bad reputation in the news for the past few summers as more and more people in cities like Dublin complain of their noise and brazenness. Reasonably rare occurrences like a gull stealing a sandwich are grabbed up by the media during quiet periods and sensationalized for attention. And of course this type of coverage helps people form negative opinions of something they might not have much direct experience of, like gulls, much the same as certain sectors of the media stir up hate with inflammatory headlines about immigrants for example. While working on a wildlife tour boat I’ve had people tell me gulls are “vermin” and the “rats of the sky” that should be exterminated. This is from people who have paid to come out to sea in the hope of seeing whales and seals and puffins (or sometimes not in hope but expectation, given that they’ve paid money and therefore will surely be reimbursed with sightings). Those other animals are ok it seems. They’ll look good on Instagram. But the gulls?! Disgusting creatures! We all have animals or plants we have a soft spot for or a particular interest in, but the idea of loving some things and hating others to the point that you wish to exterminate them speaks to the total lack of education on the natural world received by much of the wider population. Everything has its place and deserves a chance to live out its life (though I fully support the eradication of invasive species, which have their place, but in their native areas.) Herring gulls have suffered enormous population declines in the last few decades (as have the majority of seabirds, thanks to various forms of human disruption). The reason they appear so numerous in cities is because the lack of available food in our fished-out seas is driving more of these opportunistic birds to other areas where food is readily available, such as urban zones rich in litter. Granted, I don’t have gulls nesting on my rooftop waking me at four in the morning in midsummer, nor were any of my grandparents ever swooped on and frightened by a gull, but nonetheless, I find it sad that peoples’ reactions to these charming and resourceful birds are often so negative. And I lay part of the blame for that on fear-mongering “news” articles that seek to appeal to peoples’ most livid reactions in order to maintain an audience. I can’t see any way for the twin catastrophes of climate change and biodiversity loss to be tackled other than by educating people in how the world works, by which I mean the physical limitations of the planet when it comes to sustaining life. We’re straining these limits to breaking point very rapidly because people put more store in the opinion of economists (and remember, economics isn’t an empirical science, it’s a whole lot of guesswork really) than in climate, water, agriculture and fisheries scientists who gather real world, measurable data. And the data are grim. It’s utterly absurd that we’ve got to this point of living so out of touch with reality. It blows my mind and gets me down every single day. I think the generations coming up will be a lot more aware of these issues, but it’s hard to believe we’ll make the necessary changes until catastrophe leaves us no other choice. I hope I’m wrong about that.

9th April

Yesterday’s seemingly innocuous photo of two gulls certainly led me on a bit of a rant, but I think if something flows so easily while writing it’s because it was already in you waiting to be let out. Today I’ll keep it less existential, or I’ll try at least. This is a close up of a lichen known as crab-eye lichen. Lichens may seem like some of the least interesting things imaginable but they often form very interesting patterns when viewed up close. And they’re capacity to fascinate doesn’t stop with surface appearances. I’m reading Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake at the moment and learning a lot about how life on Earth wouldn’t be anything like what it is today if it weren’t for fungi. Lichens are a coming together of a fungus and alga, and sometimes bacteria, and often more than one species of each of these life forms. As such they blur the boundaries of what it means to be an individual and make a mockery of the rigid and binary classification systems preferred by the majority of scientists to date. The individuals of these otherworldly partnerships can generally manage life on their own when environmental circumstances are good, but when conditions are limiting and it makes sense to work together for the mutual benefit of everything involved lichens are formed. The fungi provide a structure as well as the ability to ‘mine’ certain minerals from the surface the lichen is attached to, and the algae can photosynthesize, producing carbon which all parties can feed on. Lichens are generally the first on the scene after new land is formed from volcanic activity, and are an important first step in making bare ground habitable for new life. Through breaking down the volcanic rock they begin the slow process of soil creation, loosening essential minerals that provide fertility for the slowly developing substrate that plants will eventually be able to take root in. And once plants are in the potential for a healthy and diverse ecosystem is huge. Some lichens are also incredibly resilient to stress and extreme environmental conditions. Certain species have been brought to space and exposed to the open atmosphere, where unfiltered UV rays are highly damaging, and temperatures can fluctuate from +120 Celsius to -120 Celsius between light and shade. After being rehydrated back down on Earth some lichens were able to start photosynthesizing again. They are a model for the strength of teamwork and partnership. And before I get into any philosophizing about that idea I’ll just recommend you read that excellent, mind-expanding book instead.

10th April

Dingle lighthouse under the Milky Way on a breezy, freezing, but beautifully clear night. Thanks to my friend Jaro for loaning me a nice fast and wide lens for this scene. The composition is a total rip off of his own idea from a few years ago too, which he once framed over dimmable LEDs so that the whole picture glowed like a TV screen in a dark room. It was one of the most creative ways I’ve ever seen of presenting a printed photograph. I’m not particularly interested in night sky photography myself, it generally requiring a higher standard of gear than I’ve ever owned, as well as a lot of computer time afterwards if you really want to do it right. It’s also incredibly difficult to reproduce scenes as your eyes saw them, which is mostly what I’m interested in for my own photography. Even this image, which is fairly boring by most astro-photographer’s standards, is way brighter than normal, with many times more stars on show than any human could actually see for themselves at night. By leaving the camera’s shutter open for long stretches of time the sensor picks up light our eyes can’t detect, giving us a view into the world beyond that which are senses are capable of seeing. I wonder if nocturnal animals, with their big, light-catching eyes, see the night skies like this? Even as a human it’s a wondrous thing to stare up into the heavens at night. To image how other creatures see the world with better eyes capable of taking in more light, as well as different types of light (lots of creatures can see UV light) is as mind-boggling as trying to comprehend all the stars in the sky.

11th April

Spring is charging ahead at a pace that’s hard to keep up with, and despite my attempts to keep photographing the various plants that represent the time of year I feel I’m bound to miss out on many of the seasonal markers. Blackthorn is one I can’t overlook though. This common hedgerow tree is unusual in that it flowers before it puts on leaves, and the bright white of its blossom against the dark colour of the wood is very striking on trees that bloom heavily. Blackthorn has a lot of folklore associated with it, or at least it used to in the days of old. According to Niall Mac Coitir’s book on the mythology of Ireland’s trees it used be believed that carrying a blackthorn stick was a good way to ward off the fairies if you were out walking at night. But using a blackthorn stick to cause harm to an animal would only bring bad luck, as the famer who struck his best cow in a fit of rage found out. Despite this latter point, blackthorn was the timber of choice for shillelaghs used in faction fighting, being incredibly hard and tough. With its sharp thorns and propensity to grow in dense thickets, blackthorn used to be planted for hedging, providing an almost impenetrable barrier for any livestock. I have heard of gardeners losing eyes while cutting back blackthorn. These days farmers put up barbed wire instead of trees, and nearly nobody is planting hedging. If they are it’s often some lifeless, non-native evergreen thing like Griselinia. In a human-dominated world what is to become of the trees and plants that have lost their magic with the dying out of folk beliefs, and for which humans find no use anymore?

12th April

The fine weather continues, still cooler than might be expected but mostly dry and bright. All the blue sky weather of the last two weeks or so has been nice to be out in but as most landscape photographers will tell you, it’s pretty boring when it comes to making interesting images of the wider world. Hence, most of my photos from the last while have been focused on the smaller details in the landscape, and with so many flowering plants starting to show around now that is no bad thing at all. So here’s another bonus photo for today; these unfurling ferns are changing from one day to the next, and while I’m sure I could find a similar one of each for tomorrow’s image I’m also happy to present both here together. Many ferns at this time of year are like little bunches of slow yawns stretching out of the soil after waking from the winter underground. The specimen on the left is a hart’s tongue fern. I always assumed it was christened for somebody with the surname Hart (and wondered about their tongue) but apparently hart was an old world for a male red deer. The fern on the right is bracken, looking for all the world like a personified cartoon version of itself with its head thrown back and arms outstretched in a deep yawn after its long sleep.

Find Part 9 here

Comments

By Lewis Rush: Thanks, Richard, for the work and information you are putting into this lovely series.

By Lewis Rush: Thanks, Richard, for the work and information you are putting into this lovely series. By Jasmine: Lovely photos rich! You are now in my esteem the pied piper of basking sharks ☺️

By Jasmine: Lovely photos rich! You are now in my esteem the pied piper of basking sharks ☺️